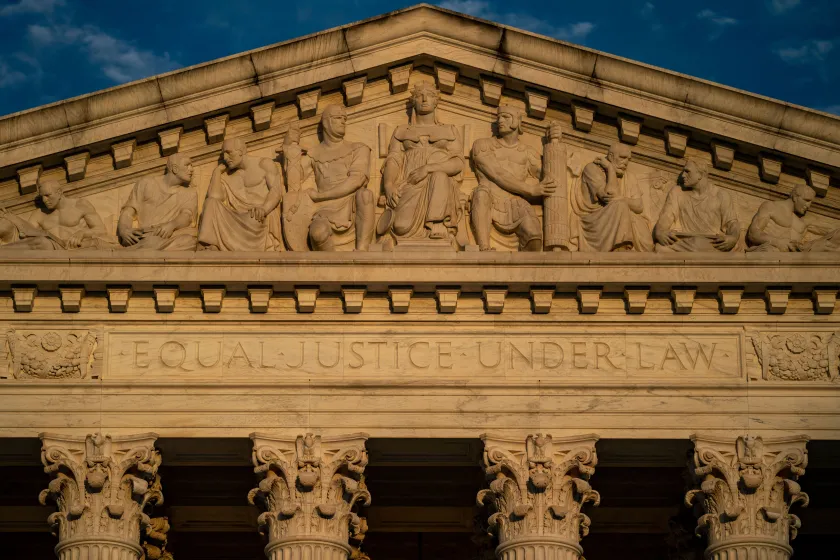

Four things students need to know after the Supreme Court ruled against affirmative action

Here are four things aspiring college students of color and their families should know about what changes to expect in the admissions process.

By Nicole Acevedo, Sandra Lilley, Emi Tuyetnhi Tran and Cora Cervantes

The Supreme Court ruling that selective colleges and universities can’t use race as a factor in admissions comes as the nation’s students have become increasingly more diverse.

Over half are Latino, Black, Asian American or Native American, said Michele Siqueiros, the president of the Campaign for College Opportunity, a nonprofit group helping Californians go to college.

“We have more eligible students ready for college than we’ve ever had,” Siqueiros said.

At the same time, Black and Latino students are still underrepresented across selective and highly selective colleges and universities institutions where fewer than half of applicants or fewer than 20% are accepted, respectively. They’re also underrepresented in many states’ flagship universities.

We asked experts to assess what the Supreme Court ruling means for students and families.

Does the ruling get rid of diversity in selective colleges’ admissions?

No.

While the ruling focuses specifically on barring race as a factor in admissions, it doesn’t limit institutions’ outreach, engagement, retention or completion strategies aimed at enrolling diverse student bodies, said Deborah Santiago, the CEO and a co-founder of Excelencia in Education, an organization that promotes Latino college completion. “You can do all of those things in these communities,” she said.

Higher education scholars and counselors say the onus is on colleges and universities to ensure that their applicant pools include students of color — many of whom come from segregated school districts with fewer resources.

“One of the things that could shift is, really, how admission officers recruit around the country, because if you can’t take race into account, the only thing you really can control is how diverse your applicant pool is,” said Angel B. Perez, the CEO of the National Association for College Admission Counseling.

Zamir Ben-Dan, an assistant law professor at Temple University, said higher education institutions will be able to continue to “promote diversity based on background, based on socioeconomic experiences,” among other experiences.

A wide array of experiences can still define what it means to have a diverse student body — including students’ experiences, where they grew up and their areas of interest. When it comes to social and economic diversity, having to work while in school, being raised by a single parent, going to a private high school on a scholarship or even experiences with the family court system “are still very unique experiences that are going to shape how a student views the world,” Ben-Dan said.

Have previous bans on race-conscious admissions affected student diversity?

The short answer is yes.

State-level bans on using race-based affirmative action in Arizona, California, Florida, Idaho, Michigan, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Oklahoma and Washington have already given the country a glimpse of the consequences of prohibiting such a practice.

Research shows that in those nine states, the enrollment of students from underrepresented communities declined, even if other factors, such as class, were weighed more heavily.

In California, data showed that affirmative action helped Black and Latino university students.

Siqueiros saw a big decline in the number of Black and Latino students who applied to selective universities and colleges after the state banned affirmative action in the 1990s.

“There was a very real reaction from high school students who just chose not to even apply. There was also a dip in the number of students who applied, were admitted and chose not to enroll, compared to previous years,” Siqueiros said.

Henry Perez, 46, a Los Angeles resident who entered UCLA in 1995 and is the executive director of the nonprofit organization InnerCity Struggle, remembers being part of “one of the last, if not the last,” affirmative action classes in the public education system in California.

Perez said he saw the sharp decline of students of color, particularly Black and Latino students, in UCLA and the University of California system. “It was devastating — we saw diversity really, really go down.”

Siqueiros now worries that the same pattern may echo across other states following the Supreme Court’s ruling.

“There is a very real message that is being heard by students about whether they belong and whether they’re welcomed at campuses,” Siqueiros said.