Pressure mounts to appoint Black, female judge to South Florida federal bench

Miami Herald staff writer Jay Weaver contributed to this report.

ome eight or nine years ago, Southern Poverty Law Center lawyer Bacardi Jackson took two of her children to the Wilkie D. Ferguson Jr. Courthouse to meet her Black colleagues. Among them was Marcia Cooke, the first and only Black woman appointed as a federal judge to the Southern District of Florida since its inception in 1847 — a distinction Cooke held until she died in January. “As we were leaving the courthouse, one of my sons looked up at Judge Ferguson’s picture and innocently asked: “Mommy, are all of the judges here Black?” Jackson said. “I decided to spare their innocence.”

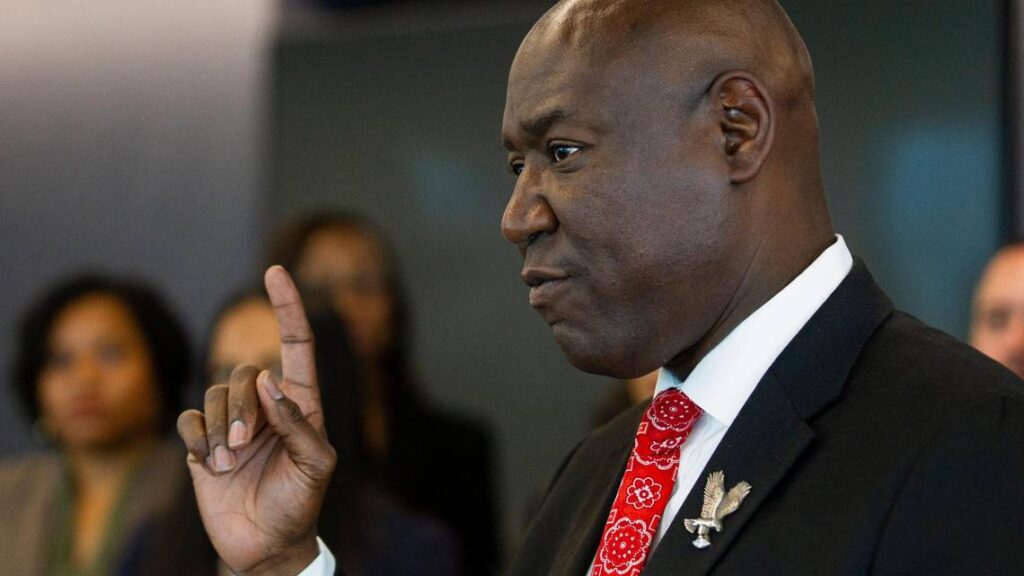

In the wake of Cooke’s death, Jackson was one of the two-dozen or so Black lawyers who joined civil rights attorney Benjamin Crump Tuesday in Miami to call for President Joe Biden to appoint a Black woman to one of the three open federal judgeships in South Florida. Crump is known nationally for championing cases of high-profile police brutality and other race-related cases, most recently representing the family of Ajike Owens, a Black Florida mother who was gunned down by a white neighbor earlier this month. Until Cooke’s death, there were only two seats open on the South Florida federal bench. After Oct. 31, Judge Robert Scola Jr. will assume senior status, which will leave a fourth opening.

Now, many are calling for Biden to choose a Black woman to fill at least one of the open spots. And appointing a Black woman to her seat was Cooke’s dying wish, Crump said. “We shouldn’t have to imagine what a Black woman sitting on the federal bench in the Southern District looks like after Judge Marcia Cooke left us,” Crump said at the Carlton Fields law firm in downtown Miami. “We should see it.”

SOUTH FLORIDA OPENINGS PILE UP AMID POLARIZATION

Biden made headlines last year for nominating the first ever Black woman to the Supreme Court, Ketanji Brown Jackson, who is also a Miami native. Civil rights groups have praised him for choosing to diversify his judicial nominations across the country. In contrast, former President Donald Trump was often criticized for an overwhelmingly white, male pool of nominations.

Though speakers directed comments toward Biden in his power to make an initial appointment, the final authority will ultimately lie with Florida’s senior Republican Senator, Marco Rubio, who has the power to withhold what’s known as a blue slip, which can shelve appointments, no questions asked. In 2021, a nominating committee handpicked by Rubio sent a list of recommendations to Biden for the then-two open seats. At the top of the list was David Leibowitz, the nephew of billionaire and Rubio campaign mega-donor Norman Braman. Leibowitz, a former federal prosecutor in New York City who works as general counsel for his uncle’s business, was also considered a potential judicial nominee by the Trump administration but wasn’t appointed. Rubio’s committee also included Detra Shaw-Wilder, a prominent Black, female lawyer based at Miami-based Kozyak Tropin & Throckmorton, a commercial firm involved in securing a settlement for the families of the Surfside building collapse victims.

Separately, a second nominating commission appointed by U.S. Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz and other Democratic congressional members from South Florida recommended six finalists for the two openings: Shaw-Wilder, Federal Public Defender Michael Caruso, U.S. Magistrate Judge Shaniek Maynard, Miami-Dade Circuit Judge Miguel de la O, Palm Beach Circuit Judge Samantha Feuer and Miami-Dade County Judge Ayana Harris. Since Cooke’s death, a legal source with knowledge of the situation said two more names have been added as potential candidates: federal magistrate judges Jacqueline Becerra and Melissa Damian, both former prosecutors with the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Miami. The timeline for when South Floridians can expect to see the positions filled still remains unclear as Biden looks toward a re-election campaign.

Sue-Ann Robinson, a former prosecutor based in Broward County who now works with Crump, said often she’d be the only Black face in the room when criminal charges were brought before Black people.

This meant fielding questions from and offering advice to defendants who saw her as a lifeline and someone they could trust, even though she’d usually be working to prosecute them. Robinson recalls calming down a Black woman who was growing aggressive when asked to fill out a form. The woman couldn’t read — a fact she only felt comfortable disclosing to another Black person. “We can’t be everywhere,” Robinson said. “Diversity on the bench is so important not because we’re saying the person’s skin is going to change something, but because their perspective and life experience increases public confidence.”

While Crump acknowledged it’s less likely to see four Black appointees, it’s vital to see at least one, he said. It’s now left to Biden and Rubio to make it happen. “When Black people walk into courtrooms, the only thing that they see that’s Black in the courtroom cannot be themselves and the judges robes,” Crump said. “At some point they need to see a Black face.”