Activists renew calls for change after police kill Jersey City man

A police killing in Jersey City Sunday has renewed calls from social justice activists who say mental health professionals, not police officers, should respond to calls involving people going through mental crises.

Sunday’s fatal encounter came five months after Paterson police shot and killed a man whose family said was exhibiting signs of mental illness, and nearly one year after a similar police shooting led to the death of a 22-year-old man in Englewood. After both killings, activists said police are not equipped to handle people dealing with serious emotional distress.

The state Attorney General’s Office has in recent months expanded a two-year-old program called Arrive Together that it says will help reduce the use of force by law enforcement during episodes like those. The program, now in dozens of municipalities across the state, pairs plainclothes officers with mental health screeners.

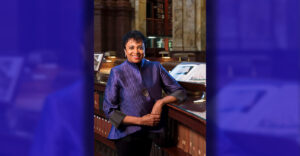

Raquel Romans-Henry is policy director at faith-based group Salvation and Social Justice, which has advocated for using community-based response teams to deal with the types of calls that ended in Sunday’s killing of Andrew Jerome Washington, 52, in Jersey City.

“There’s no emphasis on community-led solutions and inserting people who understand the community. That’s where we see things are falling short, and I think how we find ourselves in these situations,” she said.

Washington’s family members said they called Jersey City Medical Center’s intervention hotline on Sunday to come to his home because he was having an episode, but authorities say hospital workers deemed the situation unsafe and called police.

Police standing outside Washington’s door tried to communicate with him for about an hour, then when they forced open the door, Washington lunged at them, according to law enforcement. One officer used a taser and another shot him, authorities said. Officers recovered a knife near Washington, they said.

ersey City Mayor Steve Fulop said he has seen police body camera footage from Sunday and insists cops acted appropriately. Fulop, a Democrat seeking to become governor in 2025, said the medical professionals on the scene determined the situation was not safe for them, and he commended law enforcement’s attempts to de-escalate.

“Once it’s deemed unsafe, it doesn’t matter what program you have in the country as a model. No social worker will enter an unsafe room where there is potential for somebody to be harmed,” he said in an interview. “That is standard procedure everywhere.”

The shooting is being investigated by the Attorney General’s Office, which probes all officer-involved shootings and has yet to release the body camera footage from Sunday. Fulop said the officers’ actions will be justified by what’s seen on that footage.

He said the city will “explore other programs on how we can improve, and we’re always going to review how we can do better. But in this situation … the team that arrived followed protocols and best practices.”

When there’s a mental health crisis, we need action. Inaction is what has us in this place right now.

– Pamela Johnson, director of the Anti-Violence Coalition of Hudson County

Police officers’ use of lethal force when confronting people with mental health issues has come under sharp criticism, especially in the last year.

Najee Seabrooks, a 31-year-old anti-violence interventionist in Paterson, called police for help on March 3 while he was suffering what his family characterizes as a mental illness episode. Authorities say that after spending hours barricaded inside his apartment’s bathroom, Seabrooks exited the room and lunged at officers with a knife. They shot and killed him, a death that caused an uproar in the city and led to the state takeover of the Paterson police department.

Last September in Englewood, police fatally shot Bernard Placide Jr. during what officials called a domestic violence disturbance. His family has argued that authorities failed to realize he was actually suffering from an emotional breakdown, according to northjersey.com. His family has filed a wrongful death lawsuit.

Both men were Black.

Romans-Henry called it frustrating to hear authorities use the same “talking points” after these types of killings. Sending police officers to the scene at all is part of the problem, she said.

She wondered whether the workers who responded Sunday from Jersey City Medical Center were from the community and understood its specific needs. She said some institutions may be structurally racist or have workers with unconscious bias who aren’t trained for these types of calls.

“We’re saying we need to break away from that allow the community to assess the individual because they are best equipped to assess next steps. We’re not saying it’s always going to turn out in a positive outcome. But we’re not applying every tool in our arsenal, and because we’re not doing that, lives are being lost,” she said.

Pamela Johnson, director of the Anti-Violence Coalition of Hudson County, also criticized Jersey City’s response. Mental health workers should have been equipped to de-escalate the situation without exposing Washington to police, she said, noting he had been shot by Jersey City police in 2012 (Fulop said cops responded to his home several times this month).

“We need action towards creating a response that doesn’t result in death. When there’s a mental health crisis, we need action. Inaction is what has us in this place right now,” Johnson said. “I guarantee you when you try nothing, that won’t work.”

Jersey City’s council in April 2022 approved plans for a community crisis response team to deal with certain 911 calls. It has yet to begin operating. Fulop said the city has tried to seek vendors for the program twice: the first time, no one expressed interest, and the second time, Jersey City Medical Center proposed a $4 million contract, more than three times the amount the city proposed to spend.

“The outcome on Sunday it was a terrible tragedy that someone lost their life. But it wouldn’t have changed the outcome of the situation. The medical professional crisis intervention team were the first on scene,” Fulop said.

Romans-Henry commended the attorney general’s actions in this area, pointing to the office’s takeover of the Paterson Police Department and programs like Arrive Together. The program is up and running in Newark, East Orange, Atlantic City, Plainfield, New Brunswick, and dozens of others. Bayonne, Jersey City’s neighbor, is the only Hudson County city taking part now.

This year’s state budget includes $10 million intended to expand the program to all 21 counties.

“Bringing Arrive (Together) statewide to every community in New Jersey relies on strong and willing partnerships with local government,” a spokesman for the attorney general said in a statement. “We would welcome the opportunity to collaborate with the police department and the service providers of Jersey City to bring this incredible program to the city’s nearly 300,000 residents.”

Fulop said budgetary constraints have kept the city from taking part in Arrive Together, saying it would lead to increased manpower and overtime the city can’t afford, he said.

“We’re always in support of trying things, but we can’t have other unfunded programs,” he said.