Tuskegee Airman, 102, recalls historic flight training during World War II

By Bernard S

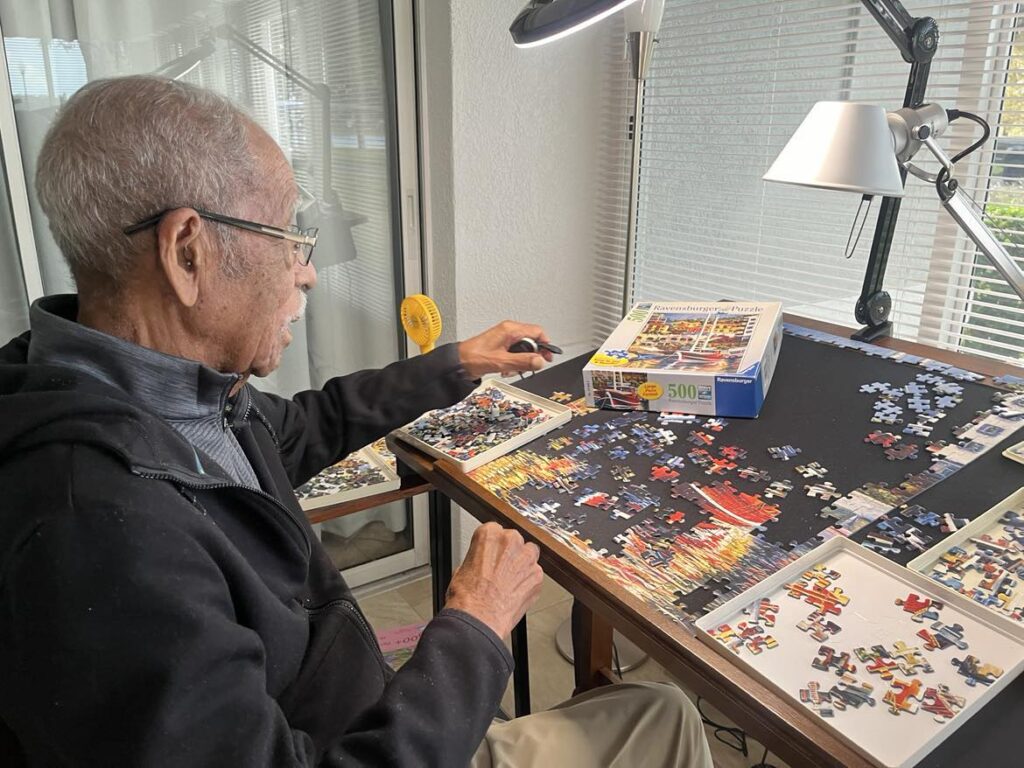

At the pivotal age of 102, Daniel Keel’s sense of humour, wit, personality and charm remain sharp. Keel – who in younger days flew missions as one of the storied Tuskegee Airmen – enjoys completing jigsaw puzzles, eating Filet Mignon and salmon, reading mystery novels and exercising for two hours a day at his Leesburg, Florida home.

“I wish I knew the secret to longevity,” said Keel, who lives with family members and recently visited a graduation program for young, prospective pilots. “I stretch and go walking. I’ve never smoked. I don’t drink. I love ice cream. I was an avid golfer until I reached age 96.”

The war veteran and avid pilot was honored at Florida Tech by the 99th Squadron, a nonprofit group based in Brevard that provides opportunities for minorities to learn aeronautics, for his achievements and resilience.

The acknowledgment for Keel, a Documented Original Tuskegee Airman, came a month after celebrating his birthday on Sept. 10. He was joined by loved ones during a family dinner. The centenarian was born in Mineola, New York, in 1922, and raised in South Carolina and Massachusetts, according to the TuskegeeAirmen.org website.

Keel met his future wife Barbara at a music rehearsal at Robert Gould Shaw House community center located in Boston when they were both 16. Colonel Shaw, depicted in the 1989 film Glory, led the 54th Massachusetts Infantry – one of the first Black military regiments that fought for the Union during the Civil War. The couple remained married for 74 years, until her death, Keel said.

Despite the hardships that came with being young, Black and focused as segregation was the law in much of the land, Keel set his eyes on the skies.

Keel was one of only three Black officers to earn three aeronautical ratings, meaning he was triple-rated and a top pilot during World War II. With a life spanning 10 decades, Keel, a natural storyteller, reflects on life lessons and Black representation for audiences young and old.

“I believe Black people should be represented in all industries, including aviation. I wanted to become an aeronautical engineer,” said Keel, who is considered by many to be a pioneer for Black pilots. “We’re just as intelligent as anyone else.”

The highly-respected Tuskegee Airmen were America’s first Black military pilots. Keel said only 30 people out of 300 graduated from basic training class in Biloxi, Mississippi, in the heart of Old Dixie.

“The odds weren’t in your favor,” Keel said.

Keel graduated from Boston Latin School, was Cadet 2nd Lieutenant for JROTC and attended Northeastern University in Boston. Keel was drafted as an aviation cadet in the U.S. Army Air Corps at age 20 in September 1943 as war rampaged across Europe and the Pacific.

Keel would join the 477th Bombardment Group, originally formed in 1943 at McDill Field in Florida. Keel recalled how aspiring officers underwent a psychological test lasting eight hours.

“The average age for pilots was 18-to-26 around that time,” Keel said.

Keel said he wanted to join the Airforce to fulfill his patriotic duty to serve the nation. There were other reasons too – a clean uniform, a clean bed to sleep in every night, three-course meals and 50 percent more pay, Keel said.

Keel trained as a twin-engine navigator, aerial bombardier and a basic single-engine aviator. The military vet said flying the B-25 Mitchell medium bomber as a pilot felt like driving a car in the air.

“I really enjoyed flying in the fighter (jet) more than the bomber because I was always in action and in motion. Fighter pilots can chase after other (aircrafts). There’s skill and maneuvering,” Keel said. “We flew bomber planes very close to each other in formation. We had to fly straight. The gunners had guns shooting from all directions.”

The job of a bomber pilot, though, was quite dangerous. Keel said he spent time training in the North American T6 Texan Trainer aircraft and the B-25 bomber plane.

“Bomber crews didn’t live very long. They were required to fly 40 missions,” Keel said. “The odds that you came home weren’t very good. Bomber pilots needed fighter pilots to protect them from enemy aircraft. That’s what their training was about.”

The military was still segregated when Keel joined the ranks with the Tuskegee Airmen, who trained at Moton Field Municipal Airport located at the campus of Tuskegee University and also at the Tuskegee Army Airfield.

The airmen also trained to be bombardiers at Midland Army Airfield in Midland, Texas, where Keel said Black officers were treated as second-class citizens. Even some of their white counterparts voiced disdain for serving with Black pilots.

“Black officers weren’t allowed to eat in the office club and had to eat in the cadet’s hall. They would feed all the white cadets and officers first and give Black officers the leftovers,” Keel said. “We had to ride at the back of the bus. Once you pass the Mason-Dixon line, Blacks weren’t allowed in Pullman cars.”

The Black officers were subjected to completing a gas mask drill where they had to wear the mask for four hours, from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m., during the hottest part of the day when the temperature was above 100 degrees.

Keel said he had two exposed walls and two windows in his quarters, allowing him to breathe a bit of fresh air while wearing the mask.

Keel said he was the first person to sign a letter that he and his fellow officers wrote protesting the conditions at Midland Army Airfield base. The letter was sent to the Inspector General in Washington D.C. on Sept. 24, 1944.

The incident was not declassified until 2015, according to the TuskegeeAirmen.org website.

“They tried to have me court-martialed,” Keel said, recalling the intense period. It would be one of a number of episodes that would draw attention to the plight of Black Americans fighting to protect a nation that, through its laws, treated them as inferior.

The military remained segregated until 1948 when President Harry Truman, distressed by an attack on an Black veteran by police in South Carolina, issued an executive order to desegregate the armed forces. The move was one of several pieces of history that sparked the Civil Rights Movement that would occur years later.

“I am asking for equality of opportunity for all human beings, and as long as I stay here, I am going to continue that fight,” Truman would later write in response to the backlash his order drew from pro-segregation politicians and others.

But before the order to desegregate, the struggle continued.

“White people would fight for their country. Black people would have to fight for their country, plus their own rights,” Keel said of the segregated military. “Blacks were assigned to the post office, laundry, assembling parts on ships and digging ditches. Everybody was watching these guys, hoping they would fail.”

But his focus grew stronger.

Keel “earned his wings,” meaning he successfully completed training and received his pilot license, in September 1945, according to a 2015 interview published in the Library of Congress.

World War II ended before the 477th Bombardment Group could be deployed to serve in the Pacific Theatre. Keel left the military in February 1946.

Keel said at the end of World War II, the U.S. military had 19,000 pilots – men and women. Keel said the Tuskegee Airmen are not only the pilots, but also support personnel, cooks, nurses, lawyers, mechanics and secretaries.

“All personnel that were part of the Tuskegee Airmen experience are Tuskegee Airmen,” Keel said.

Keel then earned a commercial multi-engine pilot’s license.

But, commercial airlines did not hire Black pilots until the 1960s. Capt. David E. Harris, an air force veteran who in 1964 became the first Black pilot of a commercial airline – American Airlines – died at 89 earlier this year, according to American Airlines.

Keel would go on to get his journeyman’s license and his masters license as an electrician. Keel said he became an electrical contractor and started his own company called Strobardt in Massachusetts.

“It wasn’t easy,” Keel said.

Keel said he thinks the climate for minorities in the aviation industry is stronger today. The veteran said he has witnessed young pilots receive mentorship through groups like the Organization of Black Aerospace Professionals, along with connections through Black Pilots of America and Tuskegee Airmen, Incorporated – a national organization that honors the history of African-Americans who were in the Army Air Corps during World War II.

Keel was married to his wife Barbara for 74 years before she died at age 95. The widower has eight children, along with several grandchildren, great grandchildren and great-great grandchildren.

Keel retired to central Florida, just west of Disney World in 1998. Keel and other surviving Tuskegee Airmen were honored in March 2007 with the Congressional Gold Medal, one of the highest civilian honors bestowed by the U.S. Congress, according to the TuskegeeAirmen.org website.

Time passes.

Keel goes back to finishing his jigsaw puzzle, carefully examining every detail and filling in the missing pieces.

From selling newspapers and delivering groceries while in school, to training in the skies with Black pilots who helped America win World War II and are considered by many to be trailblazers in aviation, Keel’s personal story remains one of spirit, courage and resilience, observers say.

During the award ceremony at Florida Tech, Keel – wearing the group’s trademark red jacket – was surrounded by a group of young, fresh-eyed teens – both boys and girls. He leaned in to listen as they talked. The teens, including some who just flew their first aircraft, soaked in the moment of being with a member of the iconic Tuskegee Airmen.

Though Keel doesn’t have all the answers to life’s puzzling twists and turns, he left one piece of advice to the youth – get a good education in whatever field they pursue.

“That’s the key,” Keel said. “Work hard. Get excellent training. Get inspiration from a mentor.”