Murder Plot Reveals a Deadly Mix: White Supremacists and Law Enforcement

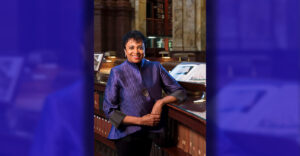

The infiltration of Klan members and other White supremacists in law enforcement has rattled much of America. (Photo: iStockphoto / NNPA)

NNPA NEWSWIRE — The lack of a federal database that tracks this type of misconduct or membership in White supremacist or far-right militant groups makes discovering evidence of intent more difficult. The FBI only began collecting data on law enforcement use of force in 2018, after Black Lives Matter and other police accountability groups pushed for more federal oversight of police violence against people of color.

By Stacy M. Brown, NNPA Newswire Senior National Correspondent @StacyBrownMedia

The FBI recently unearthed a deadly secret: top Ku Klux Klan members work in America’s prisons, holding unlimited power over inmates, including recent revelations in Florida where authorities thwarted a plot to kill a Black prisoner.

“I have long asked (Florida Department of Corrections Secretary Mark Inch), to no avail, to investigate this problem because so many of these individuals hide in plain sight,” Florida Democratic State Rep. Dianne Hart said in a statement.

“Due to the reported interest in this issue by the federal government, I will now be asking the Federal Bureau of Investigation to conduct a thorough investigation into this matter and give recommendations to the Florida Legislature,” stated Hart, the Tampa native who’s affectionately known as “Miss Dee.”

Rep. Hart reacted to the revelation of a deadly plot by Klan-affiliated corrections officers to kill an African American inmate.

The would-be murder failed because the FBI had a confidential informant inside a Ku Klux Klan operation that planned the killing.

It involved Warren Williams, a Black man serving a one-year sentence for assaulting a police officer.

The court ordered Williams to receive mental health treatment.

When confronted by White prison guard Thomas Driver, who degraded Williams by repeatedly blowing smoke in his face, the inmate and the officer began fighting.

As other guards responded, they pummeled Williams, who required hospitalization.

Angered, Driver met with fellow Klansmen and determined that Williams should die upon his release from prison.

An informant recorded all of the conversations between the Klansmen – three were involved in the plot – and made arrests.

Driver received four years in prison for his role in the plot, while his co-conspirators Charles Newcomb and David Moran got 12 years for the 2015 plot.

This year, Driver will complete his four-year sentence.

The infiltration of Klan members and other White supremacists in law enforcement has rattled much of America, particularly in the wake of the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis last year.

During the January 6 domestic terrorist attack on the U.S. Capitol, the FBI found that many of those involved were law enforcement or ex-military members.

But, the concerns about racists patrolling America’s streets and prisons aren’t new.

According to the 10-page document, White supremacist groups have historically engaged in strategic efforts to infiltrate and recruit members from law enforcement communities.

Current reporting on attempts reflects self-initiated efforts by individuals, particularly among those already within law enforcement ranks, to volunteer their professional resources to White supremacist causes with which they sympathize.

“White supremacist presence among law enforcement personnel is a concern due to the access they may possess to restricted areas vulnerable to sabotage and to elected officials or protected persons, whom they could see as potential targets for violence,” the document continued.

“In addition, White supremacist infiltration of law enforcement can result in other abuses of authority, and passive tolerance of racism within communities served.”

Reports of White supremacist groups recruiting corrections officers have emanated from Alabama and Mississippi in the South, New York and New Jersey in the North, and Arizona and California in the West.

A 2020 report by the nonprofit Brennan Center noted that the Justice Department has been delinquent in gathering data about overtly racist police conduct.

The lack of a federal database that tracks this type of misconduct or membership in White supremacist or far-right militant groups makes discovering evidence of intent more difficult.

The FBI only began collecting data on law enforcement use of force in 2018, after Black Lives Matter and other police accountability groups pushed for more federal oversight of police violence against people of color.

The Brennan report also revealed that “since 2000, law enforcement officials with alleged connections to White supremacist groups or far-right militant activities have been exposed in Alabama, California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and elsewhere.”

The continued presence of even a small number of far-right militants, White supremacists, and other overt racists in law enforcement has an outsized impact on public safety and public trust in the criminal justice system, the report’s authors wrote.

They concluded that the Department of Justice should establish clear policies regarding participation in White supremacist organizations and other far-right militant groups and on overt and explicit expressions of racism — with specificity regarding tattoos, patches, and insignia as well as social media postings.

“These policies should be properly vetted by legal counsel to ensure compliance with constitutional rights, state and local laws, and collective bargaining agreements, and they must be clearly explained to staff,” the researchers determined.

They concluded that a diverse workforce should help because it would reflect the demographic makeup of the communities the agency serves. Law enforcement leaders also should establish mitigation plans when detecting bias officers, including referrals to internal affairs, local prosecutors, or the DOJ for investigation and prosecution.

Further, the researchers suggested establishing reporting mechanisms to ensure evidence of overtly racist behavior, the employment of Brady lists or similar reporting mechanisms, and encourage whistleblowing and protect whistleblowers.

“I have heard from correctional officers, inmates, and families about how deep this problem goes,” Rep. Hart remarked.

“There are officers who are part of gangs and White supremacy groups with positions of leadership within prisons around the state. So, unfortunately, I can’t say that I am surprised by this reporting.”