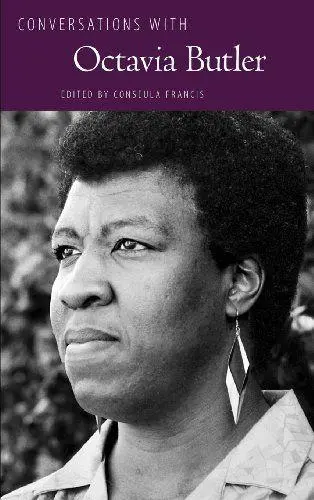

Octavia Butler, the premiere Black female sci-fi writer

4 min read

by Herb Boyd

When it comes to Black female writers in science fiction, Octavia E. Butler is singularly unique and incomparable. During her extraordinarily productive career she was a multiple recipient of the Hugo and Nebula awards, given to only the most accomplished authors in the sci-fi genre, and as a further testament to her talent, she was the first science-fiction writer to receive a MacArthur genius fellowship.

She was born on June 22, 1947 in Pasadena, California and raised by a widowed mother and grandmother in a very religious household. An extremely shy child, she spent hours in the library reading, mostly fantasy books and science fiction. These readings stimulated her desire to create her stories and she began writing as a teenager. During the Black Power era, she was a student at a community college and later enrolled in the Clarion Workshop where the focus was on science fiction. In the late 1970s she became reasonably successful as a writer, earning enough money to devote full-time to her craft. At first it was her short stories that commanded attention and soon she was the recipient of various awards, at the same time teaching in writer’s workshops. Meanwhile her writing flourished, much of it completed on the same Remington typewriter her mother bought her when she was 10 years old.

On one occasion she was watching a movie called “Devil Girl from Mars” (1954) and decided she could write a better story. She gained inspiration from the Black Power Movement and she later parlayed the spirited activism she experienced into novels that defied being subservient. Her first attempts at writing a novel took fire and in the late ’70s came a string of fairly successful books, including “Patternmaster,” “Mind of My Mind,” and “Survivor.” With the publication of “Kindred” her reputation was firmly established. “Wild Seed” followed in 1980 and “Clay’s Ark” in 1984.

She garnered her first Hugo Award in 1984 with “Speech Sounds,” a short story, and a year later won the Hugo Award with “Bloodchild,” as well as the Locus Award, and the Science Fiction Chronicle Award for the Best Novelette. Her next endeavors were far more adventurous and resulted from her travels in the Amazon rainforest and the Andes Mountains. “Dawn,” “Adult Rites” and “Imago” were her creations from the experience and arrived in the late ’80s and named the “Xenogenesis” trilogy. Her fame was solidified in the early ’90s with the publication of “Parable of the Sower” and “Parable of the Talents,” and subsequently paving the way to the MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, a prize of $295,000.

All the news wasn’t good, and in 1999 her mother died and Butler moved to Lake Forest Park, Washington. More awards were soothing and she continued the series of “Parable” books. However, the process became too stressful and she shifted to writing something lighter and thus began “Fledgling,” her last book, a vampire novel.

It should be noted that in the early days before becoming deeply absorbed in sci-fi, she was a voracious reader of comic books. This was disclosed during a panel discussion at MIT in 1998 with Samuel R. Delany, another esteemed sci-fi writer. They exchanged views on various topics and both later shared their love for comic strips and books. “When I was a kid,” Butler began, “I lived on comics. My mother actually went into my room one night or one day when I wasn’t home and ripped all my comic books in half. A familiar experience, I suspect, for anybody growing up when I was because they were supposed to rot your mind. When I was reading comics, comics had a lot more language, a lot more words, and a lot more story. It wasn’t just Jack Kirbyesque people swatting other people and standing with their legs four feet apart. And gradually, it became just that, so that there were fewer and fewer and fewer words, less and less story, and a lot more people beating each other up or wiping each other out.“

It’s hard to imagine Butler ever having writer’s block and depression, but they led to medication, which only exacerbated her problems. Even so, she managed to forge ahead with teaching and was later inducted into the Chicago State University’s International Black Writers Hall of Fame. She died outside of her home in Lake Forest Park on February 24, 2006 at 58. It was reported that she had suffered a stroke, and another account said she had fallen and hit her head.

Over the years she had maintained a relationship with the Huntington Library and bequeathed her papers and manuscripts, photographs, and other memorabilia to the library. The collection totaled nearly ten thousand pieces in 386 boxes, along with a sundry other personal items, all of which was made available to scholars and researchers.